Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy released the Trump Administration’s plan for a “Brand New Air Traffic Control System Plan” today. They want to spend a lot of money to modernize technology quickly, things that airline stakeholders will be on board for, without addressing institutional failures that created the mess in the first place. That means they’re likely to make some progress (money does that!) but not accomplish nearly what they hope.

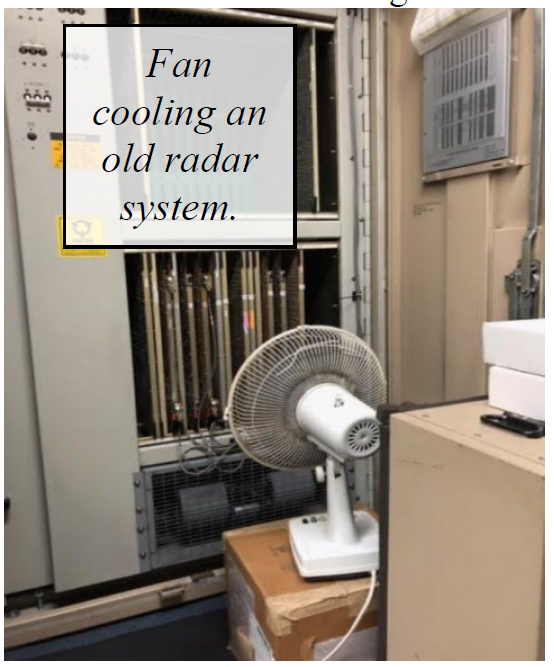

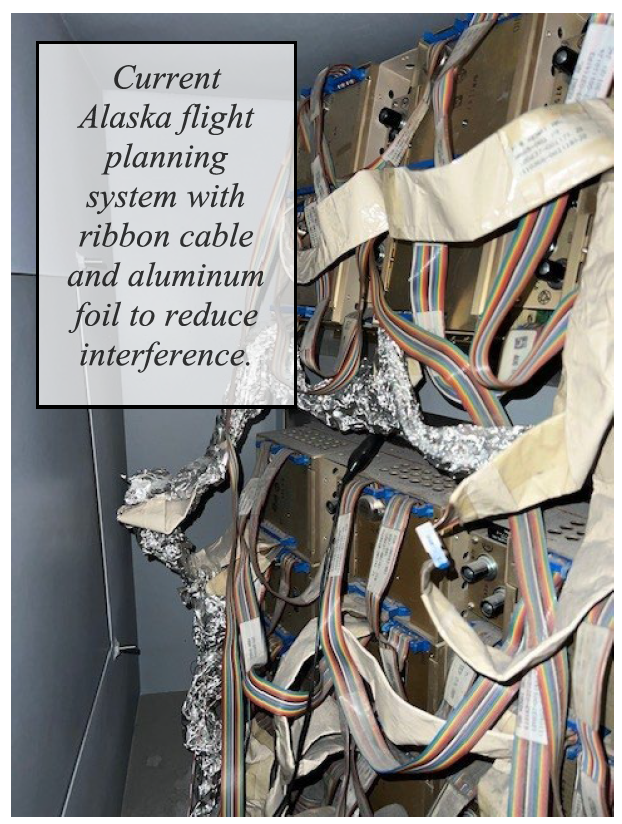

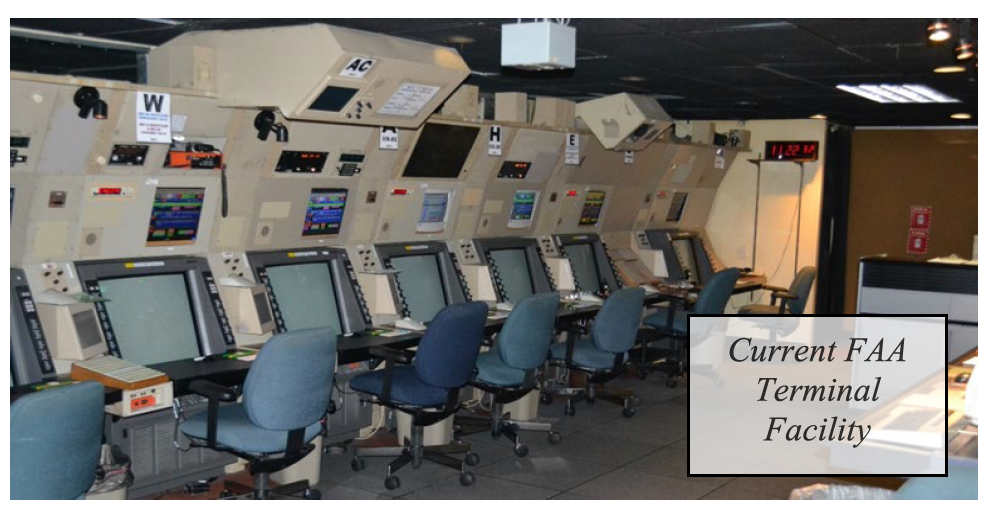

There’s no question we’re dealing with a crumbling system. That’s the fault of the FAA (how the system is managed) and Congress (poor funding models, no accountability). We’re literally decades behind NavCanada, with nearly 40% of systems “unsustainable” according to the Government Accountability Office.

The DOT does a simple job both telling and showing why there’s going to need to be an investment here. As it is, there are 300 near-collisions per year.

Here’s what’s in the plan:

- Funding request: They want a one-time 3-year supplemental appropriation but the document doesn’t specify an amount and I’ve re-read it several times. The $12.5 billion passed by the House has been described as a ‘down payment’ on this plan.

They also want a dedicated ‘capital account’ which, in terms of budget structure, is important. NavCanada issues bonds to pay for long-term upgrades, and pays off the bonds with user fees. The FAA’s Air Traffic Organization relies on annual congressional appropriations to fund long-term upgrades which doesn’t work as well.

- Major changes recommended over 3 years: Accelerate migration of telecommunication circuits at 4,600 sites to IP fiber/wireless before carriers sunset copper – the current plan likely doesn’t complete this until 2038. They want to replace 25,000 analogue radios and 800 voice switches with VoIP which is currently tracking for 2037. They will collapse 12 legacy primary‑radar configurations into at most two new models and upgrade 44 ASDE‑X/ASSC airports and deploy Surface Awareness Initiative tech to 200 additional airports.

Additionally, they want to expand ADS‑B to the Caribbean and difficult Alaskan and other remote areas and replace Traffic Flow Management System with Flow Management Data & Services software which dates back over 50 years and roll out Terminal Flight Data Manager to 89 towers (electronic flight strips replaces paper).

They would retire dozens of bespoke information‑display systems still running on floppy disks and CDs and begin design of a common automation platform that will ultimately displace both ERAM and STARS.

The plan also puts money into facilities like HVAC, roof, asbestos mitigation, pest and flooding problems and increases tower replacements from 1 per year (377 owned towers = 300‑year cycle) to 4–5 per year (80‑year cycle).

These are all reasonable things to do if your model is ‘keep the current system with all its flaws, and reward failure with more money.’ It’s largely what the airlines have been lobbying for, and what will therefore likely get support from Congress. But it’s a band-aid, and it’s far from clear that the FAA which has failed in basically every technological endeavor it’s entered in the last forty years will be able to accomplish even this in the timeline promised.

Now, air traffic control staffing remains a major problem and this plan isn’t the solution. However some improvements which started at the end of the last administration and have already been accelerated will help. The FAA is leaning into its Collegiate Training initiative, allowing training to occur at colleges where they’ve signed off on the curriculum and do audits. That helps since the FAA’s own training academy lacks the throughput to graduate the necessary controllers.

But this plan does nothing to address the core problems at FAA. While budgeting processes are a problem, they aren’t the core issue.

- The FAA’s Air Traffic Organization has no accountability because the same agency writes safety rules and runs the system. They regulate themselves. Any serious plan would split the system operator from the regulator, following ICAO best practices. (This could be done with a private stakeholder non-profit along the model of NavCanada running the system, or just putting the two functions into different agencies.)

- Creating a ‘capital account’ is good but still relies on congressional appropriations and servicing politicians rather than users and customers. A stakeholder‑run corporation could finance multi‑year capital programs outside the federal appropriations cycle, insulate projects from politics, and let airlines pay for and demand—performance.

- Modernization probably won’t succeed without cultural overhaul – Three decades of NextGen failure show how risk‑averse procurement, byzantine contracting, and lack of leadership stand in the way of progress. Pouring new money into the same culture invites more of the same.

Compressing decades of hardware swaps, software integrations, and cut‑overs into 36 months is good if it can be accomplished but also brings its own risks of service disruption. The FAA’s track record doesn’t inspire confidence.

Meanwhile, the plan doubles down on aging ground radar and deferred ADS‑B/In instead of space‑based ADS‑B and trajectory‑based operations already fielded by corporatized ANSPs abroad.

And there’s not even an attempt here to lay out the goals and metrics for air traffic control, explain what measures we expect the system to hit, and then deliver on those goals. This is more money that’s probably needed, but not everything else around it that would help get the most out of that investment. Which means this is not likely to deliver as promised.